Welcome back to Year 2049!

Join our growing group of future-curious individuals receiving the latest analysis, insights, and resources to develop a deeper understanding of the technologies and innovations shaping the future:

The intriguing jewelry store

I was at the mall last week, and one store caught my eye. It was a jewelry store. I wasn't looking to buy a ring, and it didn't look particularly different in the sea of shops around it. But what intrigued me was the giant diamond poster on the window. It said "lab-grown diamonds" beneath it.

I kept thinking about it for the rest of the day. How did they grow diamonds in a lab? Are they real diamonds? What kind of sorcery is this?

So, I decided to look for answers when I got home. Lab-grown diamonds aren't a novel concept. They've been commercially available since the 1990s. There are a couple of ways of making them:

CVD, or chemical vapour deposition, involves taking a small slice of diamond and exposing it to carbon-rich gas under high temperatures.

HPHT, or high pressure high temperature, requires pressing pure carbon within a metal cube and exposing it to lots of heat and pressure.

The results look something like this:

But here's where I learned something even more fascinating.

Some jewelry companies are now creating lab-grown diamonds using CO2 captured from the atmosphere. After all, natural diamonds are just carbon atoms that crystallized in the Earth's crust under immense heat and pressure.

One of the companies I learned about, Aether, purchases captured CO2 from Climeworks and then uses CVD to grow diamonds over several weeks. And it looks like this:

It's an ingenious way of turning the excess CO2 in the atmosphere into something useful, especially at an urgent time like today.

Our complicated relationship with CO2

The International Energy Agency (IEA) just published a report showing that global energy-related CO2 emissions reached a record-high 36.9 billion metric tonnes in 2022, a 0.9% increase from 2021.

The good news is that CO2 emissions grew much slower than expected because of the significant progress in deploying renewables, electric vehicles, and heat pumps. Those advances helped us avoid an additional 550 million tonnes of CO2 from being added to the atmosphere.

We're making progress, but CO2 levels are still at an unsustainable growth trajectory, according to the IEA. While we scale up our transition to cleaner energy sources, the world urgently needs to reduce CO2 emissions.

Mentioning CO2 naturally evokes a negative reaction. The term "greenhouse gas" is scientifically accurate but not the most endearing. In our heads, we equate it to something toxic that warms the planet. We also equate it with waste: we exhale CO2 every time we breathe, and our factories spew clouds of it into the atmosphere.

But in that waste lies the "chemical backbone of life on Earth". It's not oxygen. It's carbon. Although we can't live without oxygen, life wouldn't thrive without carbon.

The blooming opportunities of the carbon economy

My quest to learn about lab-grown diamonds led me down a rabbit hole. I discovered that captured CO2 could be used for much more than making diamonds.

Companies like Climeworks and LanzaTech, which have built carbon capture technologies and infrastructure, are now finding clients across industries who want to use captured CO2 to make their products.

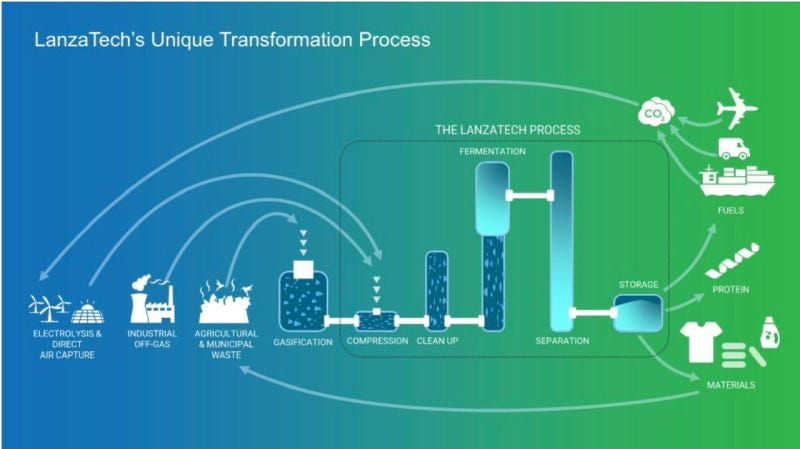

LanzaTech, a company based in the US, partners with manufacturers, oil refineries, and steel factories to capture the CO2 they emit and convert it into valuable raw materials. So far, they've recycled CO2 in several industries:

Clothing: LanzaTech has worked with Zara, Lululemon, and On (the shoe company that sponsors Federer) in creating clothing and shoes made from recycled CO2. I realize that Zara doesn't have the best reputation for its "sustainability" efforts (among many other controversies that I won't get into), but this shows that there are opportunities for other clothing brands to follow suit in their manufacturing process.

Airlines: The company also works with airlines to provide jet fuel made from CO2 converted to ethanol, which is then converted to kerosene or diesel. Some clients include Virgin Atlantic and Nippon Airways.

Cosmetics: Brands like NIVEA and Coty released moisturizers and fragrances using LanzaTech’s CO2-turned-ethanol.

CPG: Unilever launched laundry capsules, also made from captured CO2.

According to LanzaTech, the company has produced over 40 million gallons of ethanol, offsetting 200,000 metric tons of CO2. For context, LanzaTech only operates three carbon capture facilities.

While the emissions offset so far are a drop in the ocean compared to global CO2 emissions, they represent a burgeoning market that will incentivize the deployment of carbon capture technologies on a wider scale.

The challenges

Some view carbon capture as greenwashing and believe that we should focus on transitioning to cleaner energy sources that prevent CO2 emissions in the first place.

I don't see these as being mutually exclusive.

Both need to happen to achieve emissions targets. It's important to remember that cutting CO2 emissions is more complex and challenging for some industries like steel, cement, and chemical manufacturing, which account for 20% of global CO2 emissions. To put things in perspective, aviation accounts for less than 3%.

Capturing CO2 from these industries, like LanzaTech is doing, not only helps them reduce their emissions but helps other companies avoid burning additional fossil fuels to get the same raw materials.

You may be thinking: "This is a brilliant idea. Why isn't everyone doing this?"

The biggest challenge is the cost of carbon capture. Using direct air capture,it costs $600 to absorb 1 tonne of CO2 directly from the atmosphere. Climeworks expects costs to go down to $250-$300 per tonne by 2030.

Direct air capture is much more expensive because of CO2's lower atmospheric concentration. DAC plants need a constant supply of energy to capture the tiny traces of CO2 in the air.

This is why diamonds made from CO2 are a brilliant idea. Not many products can absorb the high costs of carbon capture, but diamonds have enough profit margins to make that bearable and scalable. It also comes at a time when more people are becoming aware of the ugly side of mining diamonds and are looking for alternatives. Aether claims that they can turn one ton of captured CO2 into "millions of dollars' worth of diamonds" in an interview with The Verge.

Carbon capture is much more affordable when capturing CO2 directly from the source, like LanzaTech does when partnering with factories. It ranges from $15 to $120 per tonne in these cases.

It's much easier and cheaper to catch the streams of CO2 emitted from a factory or a plant before they get into the air. And it offers a more affordable alternative for lower-margin products like clothing and cosmetics, which is what LanzaTech is already doing with brands like Lululemon and NIVEA.

Capturing and recycling CO2 is no magic bullet, but it’s an important piece of the complex sustainability puzzle.

If you enjoyed this post…

Year 2049 is a free publication and the best thing you can do to support me is to share this post with others.

If you don’t want to miss future posts, you can subscribe to get them delivered to your inbox every week:

Deep Dive

If you enjoyed today’s story, I’ve compiled some interesting readings to satisfy your curiosity:

Vote on the next deep dive

I’m torn about what I should write for the next deep dive, so you get to help me pick this time. Vote on the poll below 👇

Amazon’s push into healthcare: a look at Amazon’s entry into healthcare tech and services and their long-term strategy

The AI x AR convergence: how advancements in generative AI could help AR finally go mainstream

I’ll publish this during the last week of March

How would you rate this week's edition?

Very interesting, however how do I achieve the high temperatures and high pressures to produce diamonds from CO2? Probably by producing new CO2. And probably, but I'm not sure about this, the carbon included in a diamond is at the end less than the carbon released to produce it.

Great post Fawzi. Thanks for challenging me again and again. I find myself being underwhelmed with the anti-CO2 movement. Maybe if we were pure in all our ways I could get interested in CO2 as somehow harmful. But since we spew a tremendous amount of life threatening chemicals into our water and air and soil, and these cause very real health concerns for all living things (people alive now), I fail to see why we obsess about CO2. Wish we could make diamonds out of toxic soup.