Welcome to a new episode of Year 2049, your weekly guide to the events, discoveries, and innovations shaping the future of tech, climate, science, and more.

If this was forwarded to you, subscribe to get a new story in your inbox every Friday 👇

Happy Friday!

In last week’s episode, I shared some promising results from CRISPR trials that are currently being conducted. One of the people I spoke about, Michael Kalberer, can see colours for the first time in years after receiving a CRISPR treatment to his eyes. When I posted the episode on Reddit, Michael’s cousin happened to see it and comment on it:

“The success is very, very incremental but means everything to him”. That made my day.

As promised, this week’s episode is dedicated to discussing the safety and ethical concerns surrounding gene editing.

Hope you enjoy this one.

Design-A-Baby

Follow Year 2049: Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | Webtoon

The backstory

The heritage of humanity

Our DNA is the “heritage of humanity”, says UNESCO’s International Bioethics Committee. In 1998, the United Nations endorsed the Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights.

“UNESCO regards the human genome as the “heritage of humanity”. UNESCO believes it should be protected and passed on to future generations and that advances in science need to be considered in the light of human rights.”

– UNESCO

Concerns about editing the human genome date back to the first targeted gene-editing experiments conducted on mice in the 1980s. As you may recall from last week’s episode, CRISPR-Cas9 is our latest and best tool for gene editing and is significantly easier, faster, cheaper, and more precise compared to our older techniques.

These benefits make CRISPR-Cas9 a much more accessible technology for everyone, which also makes it easier to use for the wrong reasons. Before CRISPR-Cas9 can become a conventional and reliable tool for gene editing, it must overcome the safety and ethical concerns that surround it.

Safety concerns

Targetting the right genes

CRISPR-Cas9 is praised for its precision to edit genes and scientists describe it as a pair of “molecular scissors”. But just like us trying to cut the perfect line into our gift wrapping paper, CRISPR-Cas9 can sometimes cut a bit more than we want.

In some cases, Cas9 can cut DNA outside of the target gene, which is known as off-target editing. After DNA is cut, errors may occur in those areas where it’s being restitched together. Some CRISPR trials have reported instances of off-target editing.

The good news is that there is progress being made on making CRISPR-Cas9 even more precise. But it would be unreasonable to expect CRISPR to ever be perfect: just like any medical or scientific procedure, there is always room for error.

Further reading: Latest Developed Strategies to Minimize the Off-Target Effects in CRISPR-Cas-Mediated Genome Editing

Targetting the right cells

There are currently two ways CRISPR-Cas9 can be delivered to the human body:

Ex vivo (outside the body): scientists extract cells from a patient, inject CRISPR-Cas9 into those cells in their lab, and then reinject those modified cells back into the patient.

In vivo (inside the body): scientists inject CRISPR-Cas9 directly into a target organ.

Because in vivo treatments require an injection into the body, there’s a risk that CRISPR will modify cells we didn’t intend on changing: we could modify kidney cells instead of liver cells. At the moment, the ex vivo approach is considered safer according to Dr. Alejandro Chavez, an assistant professor at Columbia University, since the target cells are extracted and isolated when CRISPR is introduced.

However, researchers are working on developing new mechanisms to more accurately target organs such as using nanocapsules that are much more controllable and precise.

Further reading: Nano-Sized Solution for Efficient and Versatile CRISPR Gene Editing

Ethical concerns

Designer babies

The conversation surrounding gene editing always brings up concerns around “designer babies”: embryos that have been modified to change or enhance certain characteristics. This sounds like it’s straight out of a sci-fi movie, but it’s something that we can’t dismiss (yet).

If we have a tool that safely and reliably edits any of the 20,000-ish human genes, are the possibilities really endless? Our genes affect our physical traits, health, personality, and so much more. It’s still very early to say whether controlling all of these characteristics can be done safely since very few experiments on human embryos have been done.

If this is possible, there’s an even bigger concern of modifying the human “germline” (the cells in charge of producing our reproductive cells) and transmitting these changes across future generations.

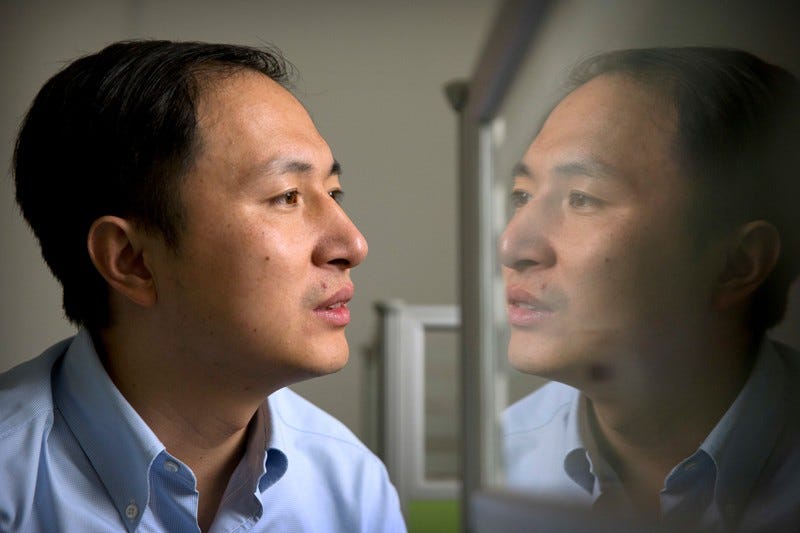

The CRISPR-baby scandal

There has only been one instance (that we know of) of babies having their genes edited using CRISPR. In 2018, Chinese scientist He Jiankui set out to help couples with HIV-related fertility problems that involve HIV-positive fathers and HIV-negative mothers. To grant genetic immunity to HIV for one couple’s unborn twins, Jiankui used CRISPR to remove a specific gene from their embryos. Later that year, twins Lulu and Nana were born and became the world’s first “CRISPR babies”.

Jiankui’s experiment caused widespread controversy in the scientific community and around the world. The Chinese government eventually sentenced him to 3 years in prison for “illegal medical practice”. The twin girls were born healthy, but they’re still too young for us to draw any conclusions about any side effects the procedure may have had on them.

Further reading: The CRISPR-baby scandal: what’s next for human gene-editing

Final thoughts

CRISPR is one of our most monumental breakthroughs in science and medicine. But like any other discovery or invention, it can be used for good and bad.

The goal isn’t to stop exploring or developing new technologies. It’s about anticipating the misuses of our inventions and setting up the right systems that prevent them from being abused as early as possible.

I’m strongly against using CRISPR for aesthetic and cosmetic purposes, especially when it can perpetuate and worsen the economic, social, and racial inequalities that are widespread today. We also shouldn’t forget that the decision to make “designer babies” will be in the parents’ hands, and I wonder how many of them would even take that risk with their unborn child if it was just for cosmetic purposes.

I’m still very excited about CRISPR. Its potential to prevent disease early, grant immunity to the deadliest viruses, and treat our seemingly incurable illnesses could truly change our lives forever.

One of UNESCO’s guidelines to implement the Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights is consciousness-raising and education, and I hope I did a good job of painting you a complete picture of gene editing’s impact on humanity.

A question for you 🤔

What can be done to minimize the potential use of CRISPR for cosmetic or enhancement purposes?

Leave a comment and let me know 👇

Help me spread the word ❤️

Doing the research, learning about new topics, making comics, and writing this newsletter has been an absolute joy for me every week.

Each edition takes about 10 hours to make, so I would appreciate it if you took 1 minute to invite your family, friends, and colleagues to subscribe to Year 2049 and join us on our weekly trips to the future!

or share this link: https://year2049.substack.com/welcome

If you missed the previous episode

Next week

I’m taking a break next week, so I’ll see you in 2 weeks!

Much love,

Fawzi

How would you rate this week's edition?

Commenting as a reproductive genetic counselor with firsthand experience counseling patients undergoing fertility treatments — CRISPR won't likely lead to extensive cosmetic or enhancement purposes given these traits are often polygenic and would involve altering many genes across the genome, many of which we don't understand fully. CRISPR is mostly good for specific target edits (good for single gene disorders like hereditary vision loss), not for common polygenic traits.

Instead, embryo selection, not gene editing, is what we should be more cognizant/wary of. By 2049, it's probably feasible for future parents to "roll the dice" and simulate 10,000 potential outcomes of what their child will have predispositions towards. They can choose to implant the embryo that most aligns with their desired outcomes.

This is a complex/nuanced topic that I feel few understand — it's much more than just whether we can make designer babies or not. Perhaps a topic for a future post on my newsletter :)